TEXT-BASED ART

in public spaces and how to read it

written by Amanda Johansson

With the constant stream of information we are all exposed to in today’s society, textual encounters in public spaces are in many ways impossible to avoid. Advertisement, traffic information and news reports are all examples of textual information we daily encounter – as well as art. Due to this constant textual feed, text-based art in our public spaces are at times passed completely unnoticed, in other cases, the opposite. Text-based art does indeed differ on many different levels from other artistic medias we are more used to encounter in public spaces, such as bronze sculptures or murals, in execution as well as in intention, but is nonetheless as present. How can one understand and read text-based art in public spaces and how can it be understood within an art historical context?

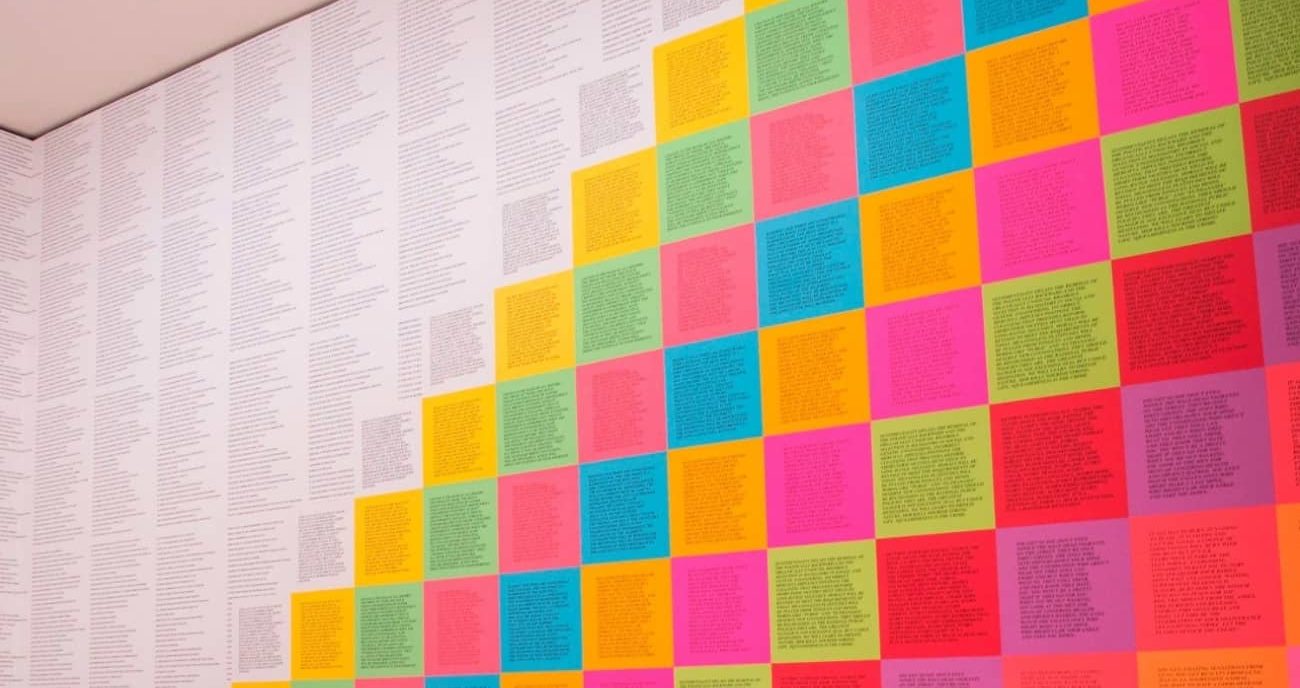

© 1983 Jenny Holzer, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Cheim & Read.

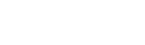

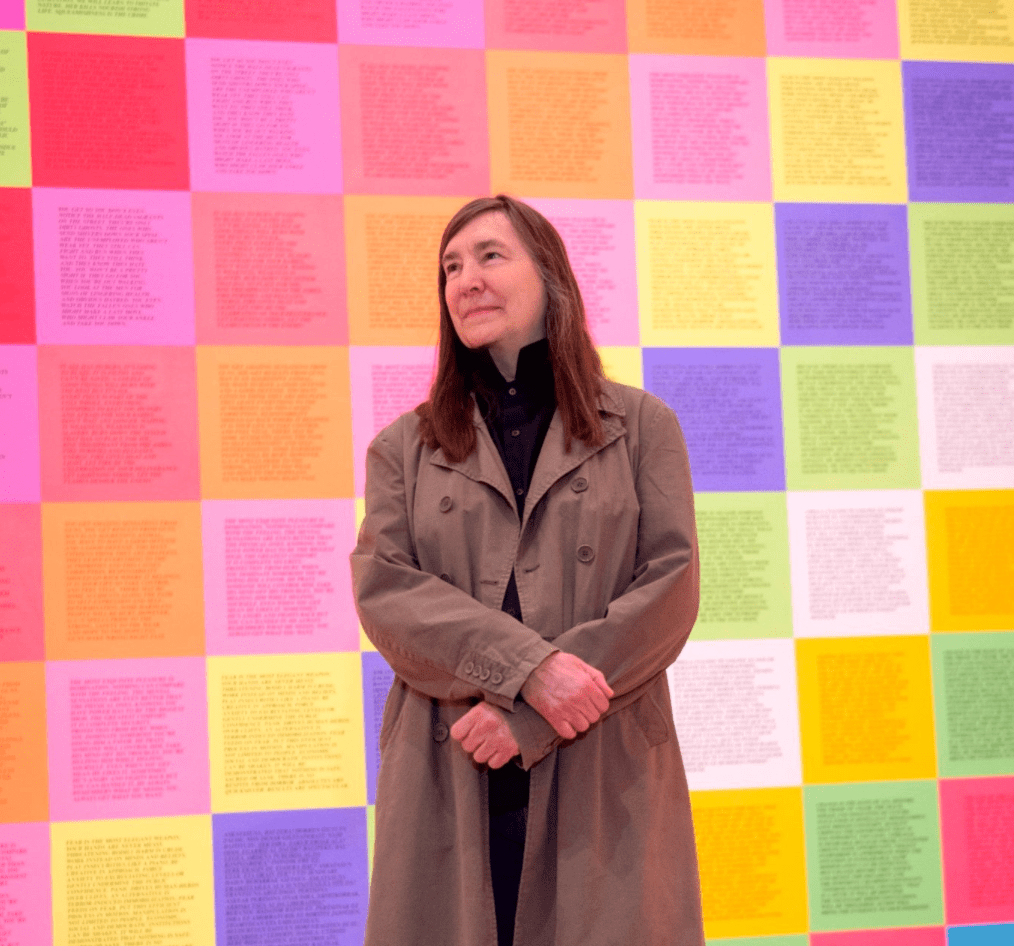

Jenny Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays, 1979-82, is a project Holzer was inspired to conduct after she had been given a reading list with readings from strong political voices, such as Mao Zedong, Adolf Hitler and Emma Goldman. Holzer created works of art by extracting and compiling small parts of the literature, composing blocks of text of 100 words in 20 lines, printed on colourful square formatted papers, which she then pastes on the streets of New York city in the darkness of night.

In Roland Barthes classical semiotic text ‘Rethoric of the image’ from 1964, Barthes explores the image, analysing which symbols create meaning in an image and how these symbols are understood and read by the spectator. To be able to conduct his studies, Barthes chose to analyse an advertisement image, arguing that advertisement both hold a strong language, or form, as well as having a strong intention and message. Barthes identifies three levels of message within the advertisement image: 1. The linguistic message (language/ text), 2. The symbolic message (connotations/ cultural associations), and 3. The literal message (objective understanding). In many ways, it is easy to find similarities between text-based art in public spaces and advertisement pictures, not only because of the use of language, but also how they seek our attention in busy spaces.

Looking at Inflammatory Essays, we encounter colour, form and text in Holzer’s work, just as we do in the encounter with an advertisement image. Without the intention of immersing into a semiotic analysis of Holzer’s work, we can take advantage of Barthes’ terminology to create an understanding of how to analyse text-based art.

In a direct encounter with Inflammatory Essays, the textual substance is what strikes us immediately (the linguistic message). The text has been written in English, meaning that sufficient reading skills in the English language is inevitable in the decoding of this artwork. The choice of language also creates associations to the role of the English language as a world language. In the encounter, it is not possible to know that these texts have been extracted from political literature, and we cannot decipher whose opinions we are reading, unless we are already familiar with the literature. The artwork has not been signed, nor is it accompanied by a statement, meaning that we cannot identify whose work we are facing. And if our reading skills in the English language is insufficient, how does this affect our understanding of the artwork? In pure text-based art, disregarding the physical material, the linguistic element also become the only symbolic element we encounter. This means, in opposition to Barthes’ analysis of the advertisement image, that we cannot separate the linguistic message from the image, but that we must see the linguistic message also as the symbolic message.

As Roland Barthes states, our connotation has strong cultural links and in text-based art, these links are based on language. Our connotation is based on cultural understandings and preconceived understandings of icons and symbols.

In text-based art, it might seem as if we in ways bypass this phenomenon, considering how easily text and letters are recognised, but then we have not considered the parameter of different alphabets in different cultures. In this example, a spectator with knowledge in the Latin alphabet, even though lacking knowledge in the English language, understand the function of the letters within a text, and can thus associate and decode the artwork differently than a spectator without understandings either for the English language or the Latin alphabet. Secondly, the letters which build Inflammatory Essays are written in a serif font, symbolizing something worthy of our attention, and elevates the importance of the text. The text is also written in capital letters, which again elevates the importance of the text. And lastly, the text is written in italics, which is also a style frequently used to enhance the importance and weight of the words. These are all examples of the symbols with which we engage with and decode differently based on cultural understandings.

If we turn to look at the last message, the literal, uncoded, “objective” symbols in the artwork, these would be the material and idiom in themselves. Black text written in capital italics, positioned in rows of 20, 100 words per piece, printed on colourful square paper. The question is if this information gives any meaning at all to our denoted understanding of the artwork, or if these even are possible to regard as uncoded, as the material in combination with the layout of the text, will be associated with warning or attention-seeking.

Barthes writes: […] we never encounter (at least in advertising) a literal image in a pure state. Even if a totally ’naive’ image were to be achieved, it would immediately join the sign of naivety and be completed by a third – symbolic – message. Thus the characteristics of the literal message cannot be substantial but only relational.

When viewing and understanding text-based art, it is indeed possible to take advantage of, and to use Barthes’ terminology, but the analysis will differ from the examination of the advertisement image as we lack a figurative element, and must thus see the linguistic message, also as the symbolic message. The literal message acts thus as an enhancement of the symbolic and linguistic message. We can ask ourselves if a pure objective literal message is ever possible to achieve, and if art can ever be seen as just paint on canvas, or like in this case, text on paper.

Inflammatory Wall, 1979–82 © 1979–82 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

_______________________________________

January 2021 I Amanda Johansson

LinkedIn: Amanda Johansson